Perri Cutten: A Timeless Legacy in Fashion

Remembering Perri Cutten: A trailblazing Australian fashion designer whose timeless elegance and...

Search...

Search...

Fashion and funerals have been intertwined for centuries. In today's society, mourning a death in the family usually calls for the most formal black outfit in the wardrobe, whereas 156 years ago, people replaced their entire closets with mourning clothes to cope with grief. From 1815 to 1915, mourning costumes were as essential and splendorous as wedding dresses. The Victorian mourning dresses represented the birth of the mourning industry, an intersection between fashion and grief.

Victorian mourning attire reflected the invisible connection between glamour and grief. The Victorian middle class adopted strict mourning dress and etiquette rules to prove their gentility and cement their class status. Women bore the brunt of the emotional labour required by the culture of mourning. In order to show their bereavement, widows spent two and a half years going through three stages of mourning; deep mourning, full or second mourning, and half-mourning. Each stage of the mourning process had fashion requirements and behavioural restrictions.

In the full-mourning period, widows were required to wear black dresses with a full-length black veil whenever they left the house. The colour black was once a symbol of bereavement as the ultimate, default fashion colour. It was the traditional colour reserved for the clergy, nuns or the bereaved, and religious groups used it to communicate their sobriety and renunciation of sin to the world. Jessica Regan, an assistant curator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, said that the "widow's weads (wead meaning garment from the old English word) had their origins in monastic dress." The purpose of wearing a veil was to act as an armour and signifier of grief for women. This veil was known as the 'weeping veil', made of a pleated silk fabric called crêpe. British fabric manufacturer Courtaulds made significant profits from producing such large quantities of crêpe. However, these veils used to cause skin irritation, respiratory disease, blindness, and even death due to the chemicals used in the manufacturing process. Widowed women were also forced to avoid social activities and events.

The most famous mourner of the period, especially for her fashion, was Queen Victoria. She wore an evening gown in the 1890s that was conservatively cut and made of black taffeta and tulle, with lace and mourning crêpe. This mourning dress reflected the traditional touches of mourning attire, which she wore from her husband Prince Albert's death in 1861 until her own death. As they transitioned to the half-mourning period, women were allowed to add a small amount of grey or purple into their outfits and could re-enter the social scene.

It was easier for men to choose their mourning clothes, as they were required to wear simple dark suits and black gloves, hatbands and cravats. Children were not expected to wear mourning clothes, although some families had their daughters wear white dresses during the grieving period.

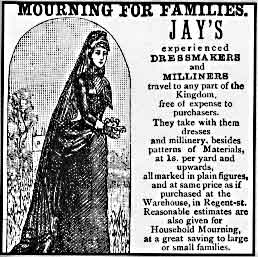

As mourners needed appropriate clothing quickly, there were many suppliers to meet their needs. The most popular one in London was Jay's Mourning Warehouse in 1841. Michael Talboys, a British fashion expert, claimed in his book The Royals that after Queen Victoria made it fashionable to wear an all-black mourning dress, Jay's Mourning Warehouse latched on to the fashion trend, producing ready-to-wear mourning clothes. It became a tradition to wear all black for the first six months with un-shiny fabric, and later people could wear shiny fabrics and black jewellery during the second six months, paving the way for the aforementioned stages of the mourning process.

The relationship between fashion and death not only reflected the intricacy of the tradition and culture of an era. The mourning clothes have become simpler over time, but the use of fashion to communicate the love and respect for the memories of our loved ones remains

By Caitlin Duan

Sources: