Perri Cutten: A Timeless Legacy in Fashion

Remembering Perri Cutten: A trailblazing Australian fashion designer whose timeless elegance and...

Search...

Search...

To become a doctor of medicine takes a level of compassion, intelligence and bravery that few possess. Beyond that, it takes a rare combination of these qualities to produce the kind of medical practitioner who goes so far above the call of duty to not only treat patients, but to completely change their lives. These incredible Australian doctors, through extraordinary feats of sacrifice and bravery, are amazing examples of people who have changed the world through medical practice.

"In suffering we are all equal"

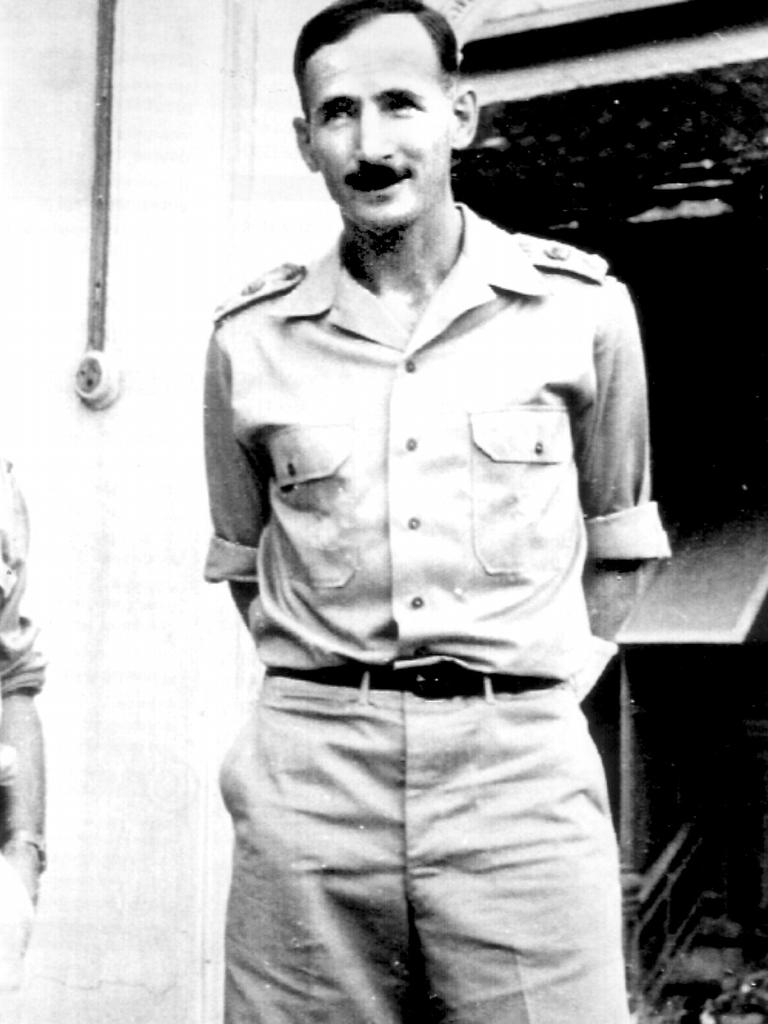

Australian World War II (WWII) surgeon Colonel Sir Ernest Edward "Weary" Dunlop is renowned to this day for his incredible story of courage, leadership, kindness and survival. By the time that Dunlop joined the army service full-time, he was on the Australian national team for Rugby Union, playing in the Bledisloe Cup, and had achieved first class honours in pharmacy and medicine from the University of Melbourne. He began his service with the Australian Army Medical Corps in 1935, having previously been a school cadet and part-time serviceman until 1929. He worked as a medical officer on a ship bound for London, where he went on to attend St Bartholomew's Medical School and later became a Fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons in 1938.

During WWII, Dunlop was acting as temporary lieutenant-colonel when he became a prisoner of war in 1942. Along with the hospital he was commanding, Dunlop was captured by the Japanese in Bandung, Java. His captors put him in command of his fellow prisoners, who were then forced to work on the famously brutal Thai segment of the Burma-Thailand railway. The conditions that Dunlop and his men worked under were deplorable, with plentiful beatings, tropical diseases and impossible expectations of productivity matched with a complete lack of adequate food, medical supplies and tools to undertake the work. However, Dunlop's courage, compassion and caring lead to him becoming a symbol of hope to his fellow prisoners - his kindness, good humour and medical expertise not only raised morale, but ensured that the Australian survival rates were the highest among all the prisoners who were subjected to the same torture. One of the men he supported referred to his leadership and kindness as "a lighthouse of sanity in a universe of madness and suffering".

Finally, his torment ended with the end of the war and he did the impossible - he forgave the people who had captured and tortured him, instead turning his efforts towards healing and devoting himself to the betterment of the health and welfare of former prisoners of war and their families. His amazing story and tireless work in several health and educational organisations after his horrific experience lead to him having a profound effect on the people of Australia and Asia, receiving honours all over the world for his incredible work in the face of pure terror.

This place will go on for many, many years until we have eradicated fistula altogether - until every woman in Ethiopia is assured of a safe delivery and a live baby.

Sydney born and raised obstetrician and gynecologist (OBGYN) Elinor Catherine Hamlin, along with her husband Dr Reginald Hamlin, have saved the lives of over 60,000 women, mostly in Ethiopia. After graduating from the University of Sydney's Medical School in 1946, Catherine Hamlin undertook several internships before becoming a resident of obstetrics at the Crown Street Women's Hospital.

When the Ethiopian government placed an advertisement in a medical journal calling for an OBGYN to establish a school of midwifery at the Princess Tsehay Hospital in Addis Ababa, Hamlin took her small family, including six-year-old Richard, and moved to the whole new world in which they found themselves in 1958. In the Western world at the time, obstetric fistulas were seen as a rarity they believed had been eradicated. As more and more women presented themselves to the midwifery school suffering greatly under the painful, debilitating and socially isolating condition, the Hamlins decided to create a dedicated hospital to treat the condition. It took a lot of time and hard work, but in 1974, the couple founded the world-first Addis Ababa Fistula Hospital.

Since the foundation of the original hospital, the couple also established five regional fistula hospitals before 2010. Hamlin didn't just stop at patient care - as part of her whole patient approach, she led a program to prevent the fistulas from occuring in the first place with quality midwifery - founding the Hamlin College of Midwives in 2007. The College funds and teaches students from rural Ethiopia in a four-year degree to earn their Bachelor of Science (Midwifery), who are then re-deployed back to their communities to care for the women there who need them. Hamlin also opened a rehabilitation and reintegration facility in 2002. The facilities not only provide care for the long-term injuries obtained from fistulas, but they also provide educational classes, counselling and vocational training.

Both Catherine and Reginald lived on the grounds and were actively involved in the day-to-day of the hospital and patient care up until their deaths in 2020 and 1993 respectively. The pair and their hospital earned numerous awards and recognition for their service to women in developing countries, as well as the deep gratitude of the people and government of Ethiopia. To this day, Catherine Hamlin is one of only three people to receive the Eminent Citizen Award on behalf of the Government of Ethiopia from the Ethiopian Prime Minister. In her honour, the Catherine Hamlin Fistula Foundation is working towards treating 100,000 women and eradicating fistula forever.

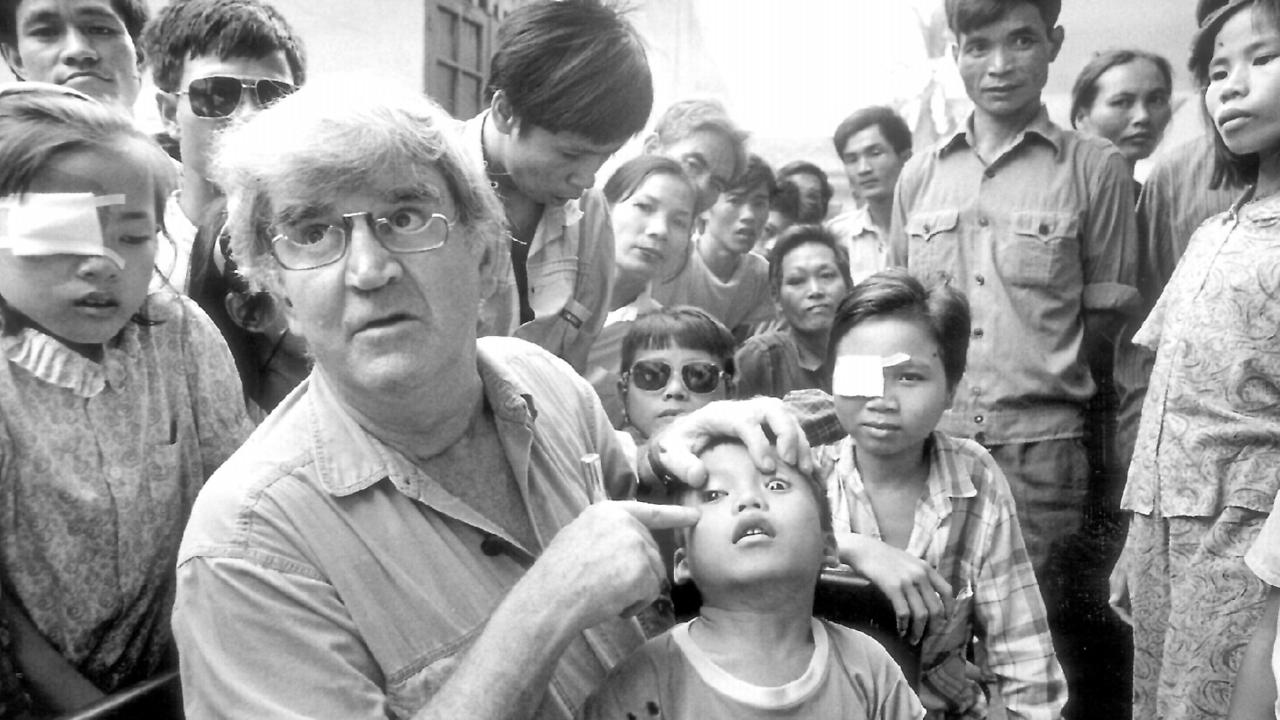

"Every eye is an eye. When you are doing surgery there, that is just as important as if you were doing eye surgery on the Prime Minister or King."

There are few around the globe that are unaware of the incredible work of the New Zealand-born, Australian ophthalmologist, Fred Hollows. Hollows began his medical career in 1961 at the Moorfields Eye Hospital in England. After undergoing his post-graduate studies in Wales, he moved to Sydney where he worked as an associate professor of ophthalmology at the University of New South Wales. He began his iconic work in the early 70's with the Gurindji people at Wave Hill in the Northern Territory. During this vocation, combined with his work in the Aboriginal communities around Bourke and other Indigenous groups, he became increasingly concerned regarding the number of Indigenous people suffering from eye disorders, including trachoma.

This inspired his life's work - to advocate for the right of Indigenous people to better their living conditions, especially regarding their access to eye health. Hollows would then go on to set up the Aboriginal Medical Service in Sydney in 1971, alongside Indigenous activist Mum (Shirl) Smith. Subsequently, he assisted the establishment of several Indigenous health services across Australia. After receiving funding from the Australian Government in 1976 until 1978, the Royal Australian College of Ophthalmologists, which Hollows organised, established the National Trachoma and Eye Health Program, which was tasked with visiting Indigenous communities to identify, survey and treat eye defects. During this time, the ophthalmologists visited more than 460 Aboriginal communities, where 62,000 Aboriginal people were examined, leading to 27,000 being treated for trachoma and 1,000 operations being carried out in just three years.

From 1985, Hollows took his pioneering work to a global scale, with his visits to Nepal (1985), Eritrea (1987) and Vietnam (1991), where he established several life-changing training programs and laboratories, designed to lower the cost of eye care for people in those developing countries. Shortly before his passing in 1993, The Fred Hollows Foundation was launched in Australia to continue his mission of providing eye care and improving the health of Indigenous Australians and the underprivileged and poor. The Foundation, registered in Australia, the UK and New Zealand, continues to carry out this important work to this day.

By Claudia Slack

Sources: