Brian Joseph Prove

Full Circle of a Life Lived in Faith.

Search...

Search...

A Tribute by John Alexander

Keith was born in Beech Forest, Victoria to Georgina May Firth (née McIntosh) and Joseph Memory Firth. Over the next seven years, Keith came to have three siblings: brother Marshall followed by sisters Jean and Betty.

In 1921, Joseph was a rising star in forestry, and to further his career, the Firth family moved to Scottsdale in northern Tasmania.

Keith attended schools in Scottsdale and Launceston and qualified for matriculation at Launceston High in 1933. In 1934, he headed south to study at Hobart Teachers' College.

As a qualified teacher, Keith was posted to several far-flung small schools. Perhaps Keith's most challenging posting was to Catamaran in 1939. He boarded 3 km away at Cockle Creek, Tasmania's damp and chilly southernmost settlement, and commuted to and from Catamaran by bicycle.

On 8 July 1940, Keith volunteered to become a soldier in the 2/40th Battalion. As 1940 drew to a close, he had what would prove to be his last Christmas at home for five years. Army training was soon shifted from Brighton (near Hobart) to the mainland, and come mid-1941, the battalion was stationed in Darwin.

Then Japan attacked Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941. On 10 December, Keith was on board S.S. Zealandia in a convoy with the bulk of the 2/40th battalion, which was by far the single largest element of the recently formed "Sparrow Force". The force was sailing north to Timor, ostensibly to defend a key airfield.

26 January 1942 brought with it the first of many attacks on Sparrow Force by Japanese warplanes. On 20 February, a Japanese convoy disgorged some 5,000 troops who came ashore in Timor in a major amphibious operation. The Japanese heavily outnumbered the allied force and were much better equipped; moreover, they had already achieved total control of the skies.

Fighting reached a peak on 22 February 1942. The Australians employed astute tactics to inflict heavy casualties on a Japanese force on Usau Ridge and blocking a key route. The action culminated in a bayonet charge up the ridge (with Keith in the thick of it) and the enemy was overrun. Some authorities have asserted that Sparrow Force's commander dithered and squandered the chance of successfully fighting a withdrawal action. In any event, the very next day, the slow-moving Australians were surrounded by a far superior force, and capitulation was the only option.

Sparrow Force had lost 48 killed in action, with 130 wounded.

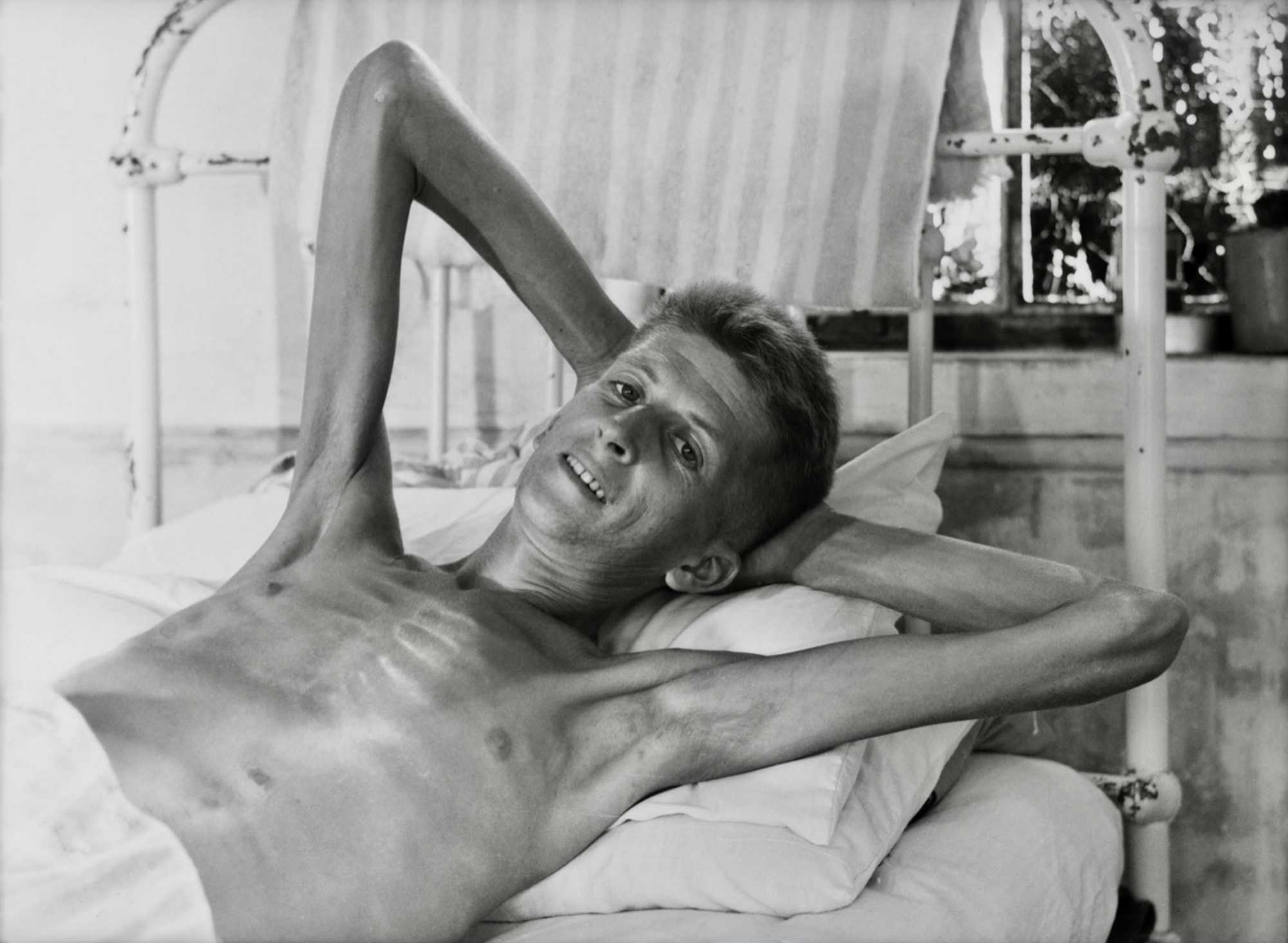

And so Keith's eternity as a Prisoner of War began. He would be afflicted by ulcers (both legs), beri-beri, malaria (24 attacks!), dysentery, and extreme malnutrition.

Initially held at Usapa Besar on Timor, Keith was among those taken to Java on Dai Nichi Maru, an aptly dubbed "hell ship". The terrible journey commenced on 23 September 1942 and the POWs were shipbound for a week.

Another grim chapter at sea began on 25 June 1944 when Keith was transported from Java to Sumatra via Singapore. In Sumatra, Keith was one of many POWs - and locals - who were forced into labouring to build a railway line through 230 kilometres of jungle. The brutal conditions claimed the lives of many a forced labourer, and the death rate was soaring when the railway was completed on 15 August 1945. On the same day, Japan surrendered. The war was officially over, but 242 of Keith's Sparrow Force comrades would not be returning home.

On 18 September 1945, Keith wrote: "On the evening of 24th August our camp commander, Capt. Armstrong of the English army and one of the finest gentlemen I have met, announced that the Japanese captain in command of prison camps in our area had informed him that the war was over and that we were free. It was an unforgettable occasion - there was no cheering, nor handclapping but rather a great sigh of relief." (This extract is from one of 11 surviving letters he wrote home while in a hospital in Singapore.)

Keith again, in the same letter: "Last night I lay on a real bed with real pillows and a real mattress and did not sleep very much because of the unnatural softness, the comfortable space between persons, and the absence of bugs and lice. (Just at this minute - 5 minutes to midday - a gramophone has commenced. Every hour seems to bring back something which I had forgotten about.)"

On 8 October, Keith was homeward bound on the Hospital Ship Manunda and on 29 October, he was back in Tasmania. Following several spells in hospital in Hobart, Keith was discharged from the army on 18 February 1946.

On 11 June 1946, Keith gained employment in the Repatriation Department (latterly the Department of Veterans' Affairs, or DVA).

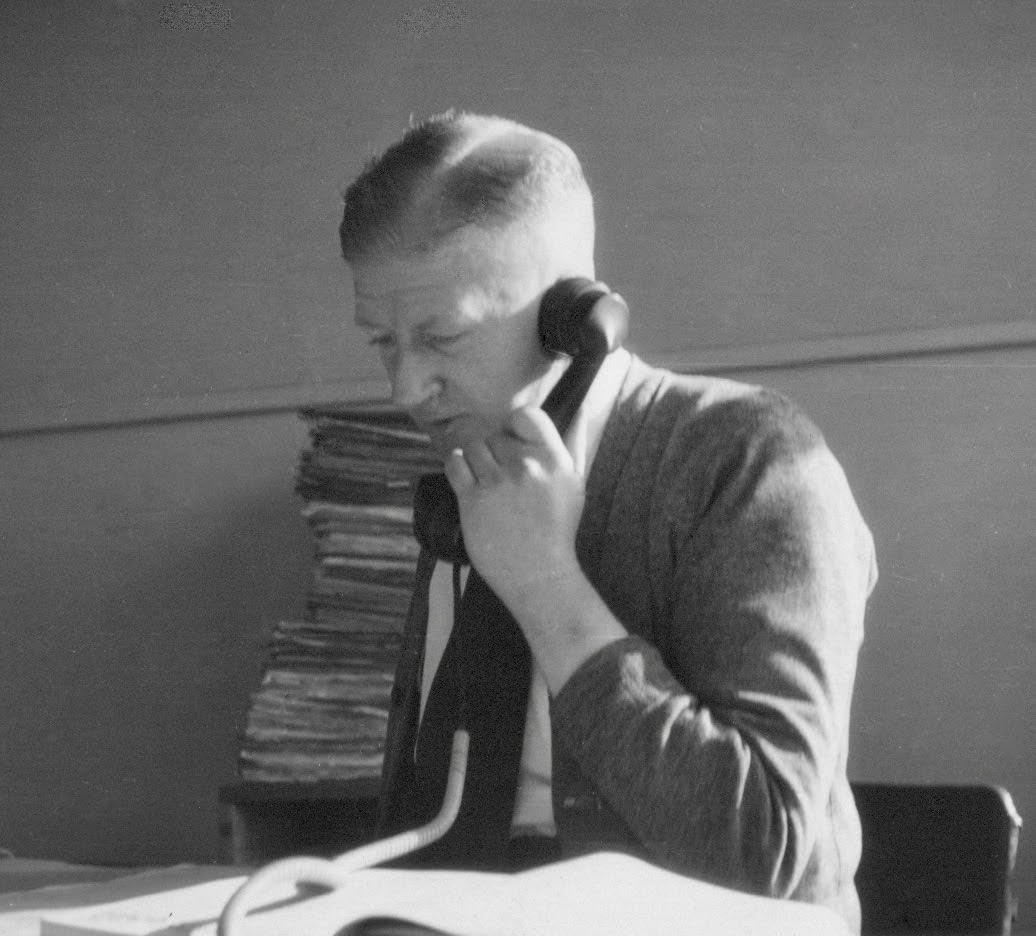

In 1967 he had become a clerk at the Repatriation General Hospital, and there are grounds for thinking that Keith had now found an ideal place where he could use his talents to assist other veterans.

As the RSL's John Paul put it in his eulogy, "Keith became somewhat of a legend throughout the ex- service community. He at all times placed the concern of any ex-service patient at the ... hospital as his first priority, and would go to any length to ensure that the patient received prompt and courteous attention on admission to the hospital and during their stay. ... Time was not a factor to Keith: he would regularly commence work up to 2 hours before he was rostered to start, and finish hours after his allotted time..." In 1977, the ever humble Keith was awarded a British Empire Medal for exceptional service.

In 1981, Keith turned 65 and had no choice but to retire from the DVA. Keith's hefty "On Your Retirement" card tells us something of the esteem in which he was widely held: 149 of his fellow DVA staff members signed the card to express affection and appreciation.

Yet Keith was quickly back in the fray, only now in the RSL as a Pensions Officer and Veterans' Advocate. His dedication to veterans' welfare remained unwavering. He continued to work long hours, and John Paul's eulogy tells us that Keith "in many cases paid for doctor's reports etc. that may have assisted a veteran from his own pocket if he considered the veteran was in financial difficulty".

In recognition of his work, Keith was made an Anzac of the Year in 1992. An inspiration to those working alongside him, Keith gave his all, right up until a week before his heart-related death. Shortly after Keith's passing, DVA Deputy Commissioner Dr R.W. MacIntyre Smith wrote this of Keith: "He was always impeccably prepared for his [RSL advocacy] cases, presented them logically and coolly, and followed up where necessary with the same methodical thoroughness. "We shall not see his like again, and he will be sorely missed as a man, advocate and welfare officer."

John Alexander, Keith's nephew, is working on a book about his life and needs help plugging a few important gaps in Keith's story. If you wish to lend a hand and knew Keith:

• While working at the Repatriation General Hospital (1967-1981)

• As a politician involved in any of Keith's RSL cases (1981-1995)

• In relation to a Veterans' Review Board or AAT (1981-1995)

• In any other way that told you something important about Keith

The book will have a strong visual quality, so please send any photos featuring Keith. If you think you may be able to help to do justice to Keith's legacy, please get in contact with John Alexander.

Email: johnaalexander@netspace.net.au

Postal Address: PO Box 232, North Hobart, TAS, 7002

Share your own story or eulogy about a loved one, online in a safe environment for future generations. Please click below.

Share their story