Brian Joseph Prove

Full Circle of a Life Lived in Faith.

Search...

Search...

The eulogy of Margaret (Peggy) Susan Brock, read by her husband, Norman Etherington

I first met Peggy some 56 years ago. I was two weeks in Australia - a starting lecturer without a PhD at the University of Adelaide. I knew nothing about the system of honours studies in Australia but I was told that one of my jobs would be to advise honours students on their research theses. Well, I knew what a research thesis was from my undergraduate days and as people came to my office and asked, 'Can I study with you?' I said, 'Yeah, sure'. The result was I found myself with eight students to advise, which was pretty intense over a period of about 8 weeks. One of those students, who looked like she's been stuffed rather than buttoned into her shirt and jeans, was Peggy Brock. She said she'd tried a few other people, 'Can I study with you?' I said 'Yeah, what do you want to do?', and that led to my being her honours supervisor on what turned out to be quite a successful thesis. People hearing the story, especially second-hand, say 'Right. New lecturer, 27 and little student, 20; love blossomed, and they were together for the rest of their lives.' But that's not how it went. It was very different and took unexpected turns.

I should say a few things about Peggy's qualities as an honours' student during those initial eight weeks. I told each of my students to come along each week and tell me what they'd done, show me the pages they'd written. The only one who ever came having done what they said they were going to do was Peggy Brock. The second thing I remember was that out of all eight students, the only one I can remember not talking about the brilliant career they were going to have and the wonderful things they we're going to do as a historian was Peggy Brock. When I asked her why she chose to study history she replied, 'Well, I want to know why things happened because if it hadn't been for Hitler I wouldn't be here'. That was a very Peggy-like comment. She was very interested in unintended consequences: things that do not go quite as planned, the good that can come out of evil, the good intentions that bring ruination. She applied this lesson in her later work. Another thing that marked her out was her willingness to enter into arguments. Other students sagely agreed with everything I said. She looked me in the eye and said 'I can't believe you said that.' No hour of supervision could be spent more delightfully.

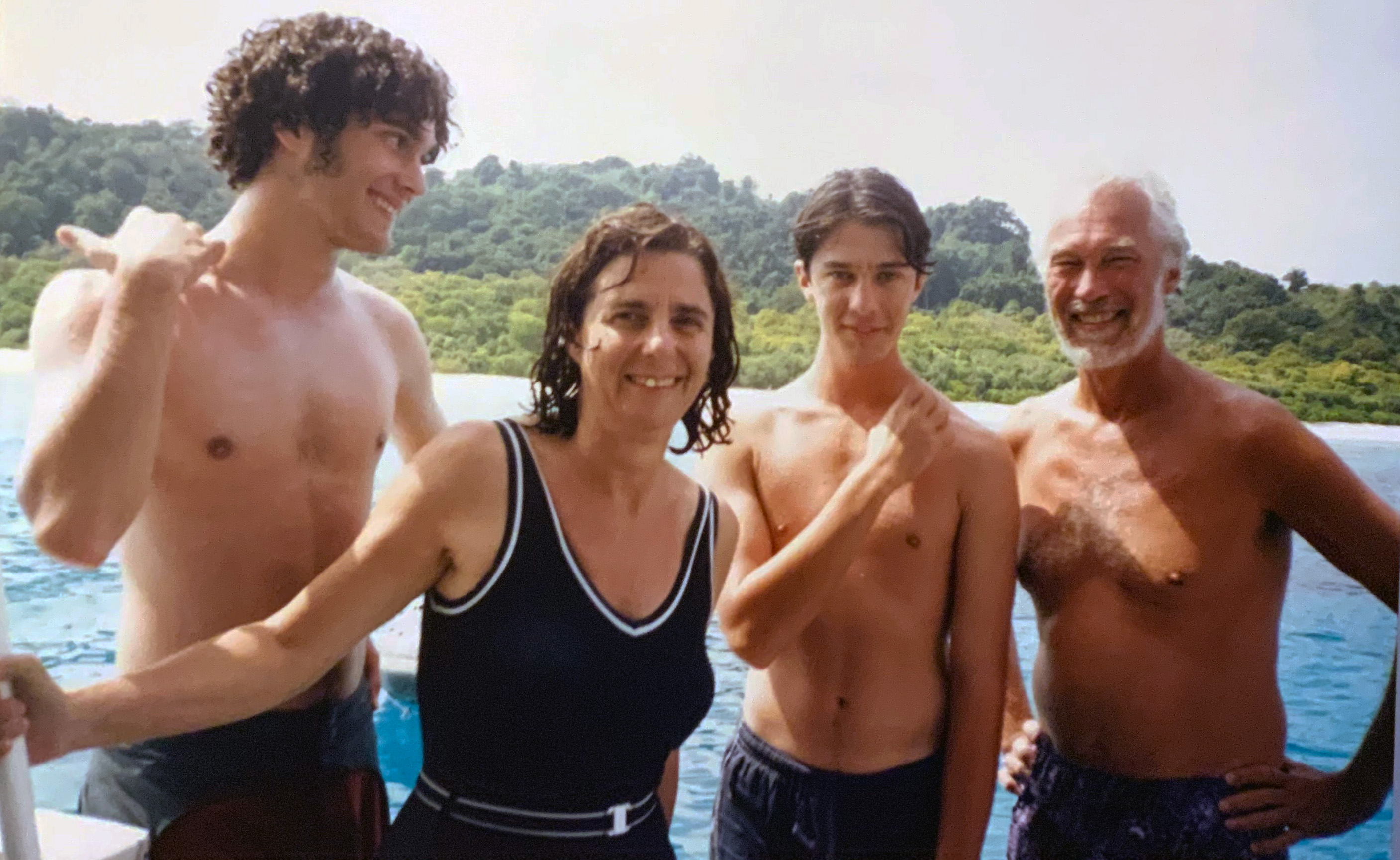

When supervision ended - I think it was about Easter time, 1969 - I said to Peggy and the others, 'Please don't just walk out of my life now', but they all did. I didn't see her for another two years. When next we met it was not in an academic situation at all, but at a party including many of friends of which Lucy spoke so eloquently. The duckling had become a swan and was living the life of an exuberant young lady. I went to more of those parties until there was one at her house in May of 1971. She asked me to dance, which was the beginning of a very big thing. At that time she was working as an archivist at Flinders University. Not long after she went off with Lucy and other friends to travel the world. When she returned 18 months later she enrolled for the Master of Planning degree at Adelaide University. Our conversations resumed and before long had gone beyond unintended consequences. In fact, we were headed towards some pretty and momentous consequences. We moved in together in 1976.

While pursuing her planning degree, Peggy got a job with the Monarto Commission, which was charged with establishing a new city near Murray bridge where the Monarto Zoo is now. She was the chief social planner - a big jump up that had me looking forward to moving to maybe Callington to be close to her. Then the Commonwealth funding fell through. Monarto was never built and Peggy found herself in the Department of Environment and Planning. At first she had a job without duties because a change of government cast her under a cloud. Having been union reps, she and her friend Carol Watson were regarded, groundlessly, as lefty radicals.

Hearing there was an Aboriginal Heritage Unit within the department, she went along and asked if they had anything for her to do as an honours graduate whose thesis concerned Aboriginal affairs. The head of the unit said, 'Well as a matter of fact there is. People in the North Flinders ranges want help with government archives to complete a history otherwise known through stories and memories.' Marrying her archival expertise with their deep knowledge, Peggy plunged into the project with great enthusiasm. That led to her first book, Yura and Udyna. Throughout a long career her happiest memories of research were those early years and the people that she met - so many of them - people she got to know well and came to our house when they were in town.

She loved going out with the Adnyamathana women and hearing their stories. They told her at one particular place that they couldn't camp, because 'after dark things happened'. She accepted their admonition and moved on. She soon realised that the women had a huge fund of cultural knowledge, largely unrecognised due to the prevailing belief that aboriginal men were the chief custodians of all things cultural. Seeing that women had a great deal of business of their own to take care of, Peggy took up that research trail, which led to another book, Women, Rites and Sites. Her goal was not to win kudos or promotion, but to experience the joy of discovery. I once asked her what she thought was the purpose of life. She replied, 'To get through it'.

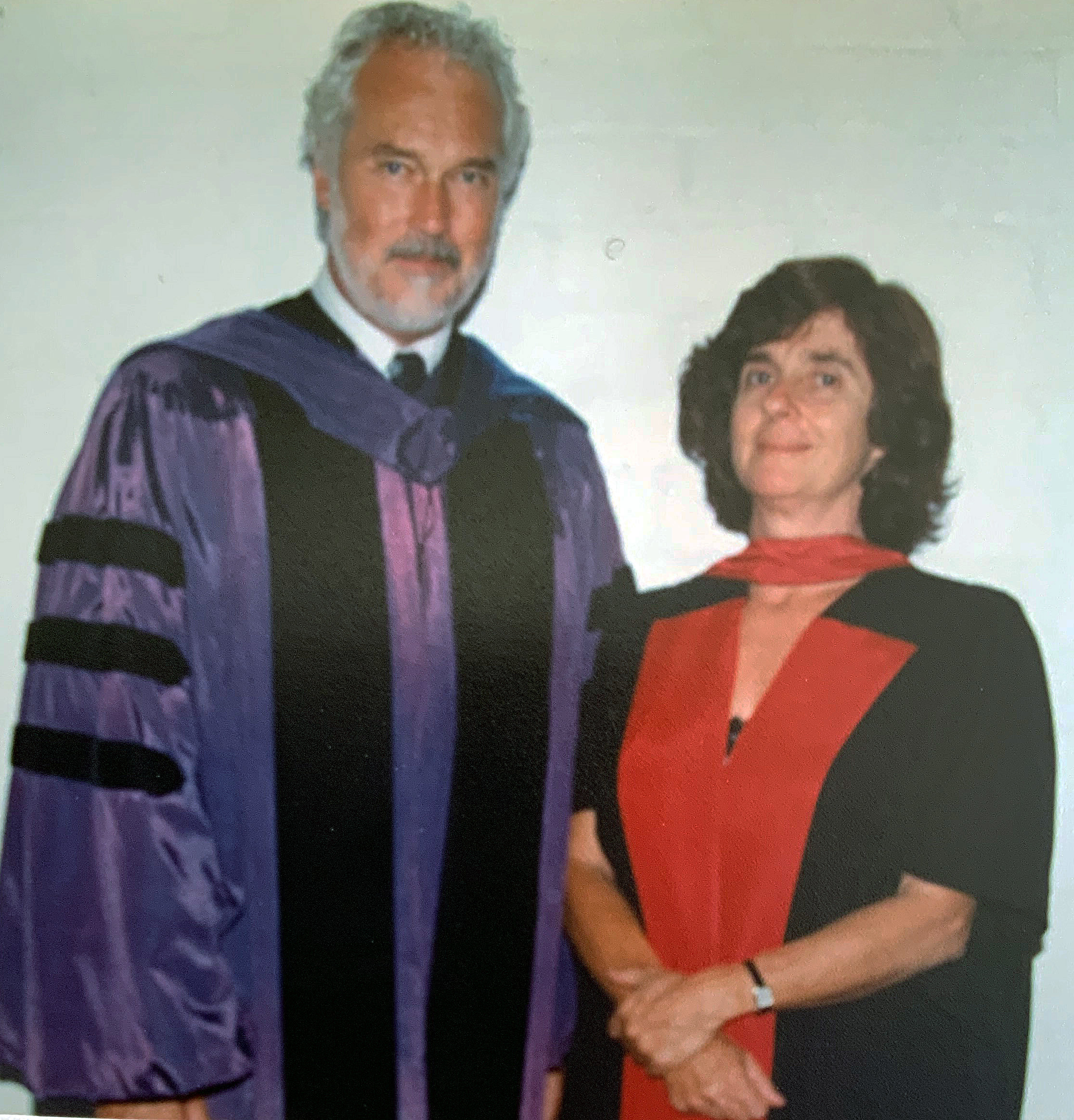

A new world had opened to her in the North Flinders ranges. As she was now engaged full time on historical research, she thought she might as well learn how to do it better. Enrolling as an MA student in history, she had the fortune to have an outstanding supervisor in Fay Gale who was then a professor of geography and later Vice Chancellor of the University of Western Australia. When I told her in 1989 that I'd been offered a job in Perth, she said, 'Well, you'll have to take it, and of course I'll go with you.' She expected she'd be working on Indigenous history in the West as there was so much to explore. But due to a collapse in the local economy, there wasn't a single job opening for her in the public service. Despite having no wish to pursue an academic career, she began doing some part-time university tutoring. That led to an appointment at Edith Cowan University where she went on doing what she liked, looking for untold stories and unintended consequences. The unintended consequence for her own life was that she became a professor of history with a long list of books to her credit. She never took much notice of her own career as long as she was having a good time and learning something.

At that point, after twenty-five years together, our research paths at last converged. I had been commissioned to edit a book on Missions and Empire for Oxford University Press. Peggy contributed one of the chapters. For the first time in our lives we were actually working together, not as student and teacher, but as colleagues and equals.

After retirement she stayed active as a volunteer for the SA Museum. If someone wanted her to make use of her knowledge, she was ready to go. For instance, when she was asked to take part in the popular TV series, "Who Do You Think You Are". Her onscreen conversations with Michael O'Loughlin and Adam Goodes struck a chord because their ancestors' experience exposed what she regarded as the most destructive aspect of post-invasion Aboriginal history: the implacable hostility of settler colonialism.

Watching Peggy carve her unique path as a historian was one joy of our life together that I am proud to share with others.

Share your own story or eulogy about a loved one, online in a safe environment for future generations. Please click below.

Share their story